A storytelling impact autopsy at Sheffield DocFest

- Written byKate Keara Pelen

- Published date 22 August 2023

Documentary and art have long been used as tools for social change. But how and why they have the impact they do is less well known.

When talking to people across the creative and social change sectors, we’re finding that our approaches to impact and change are quite different. At the institute, we plan to bring people together from these different fields to see what they can learn together. Our aim is to better understand the connection between the two and to enable storytellers-for-change to make a greater social impact through their work.

For this year’s Sheffield Documentary Festival, we co-designed an experimental event format with the help of campaigners to test out our approach with different artists in front of a live audience.

The host

Fran Panetta - Director, AKO Storytelling Institute.

The campaigners

Sue Tibballs OBE, CEO of the Sheila McKechnie Foundation, a civil society think tank and training organisation.

Zamzam Ibrahim environmental campaigner, facilitator at Julie’s Bicycle and co-founder of SOS UK.

The format

The world of campaigning uses tools and strategic frameworks to maximise and measure impact. We were curious to see how one of these tools might map on to creative projects and processes – not just documentary film – in a useful and enlightening way, for the artists themselves and for their audiences.

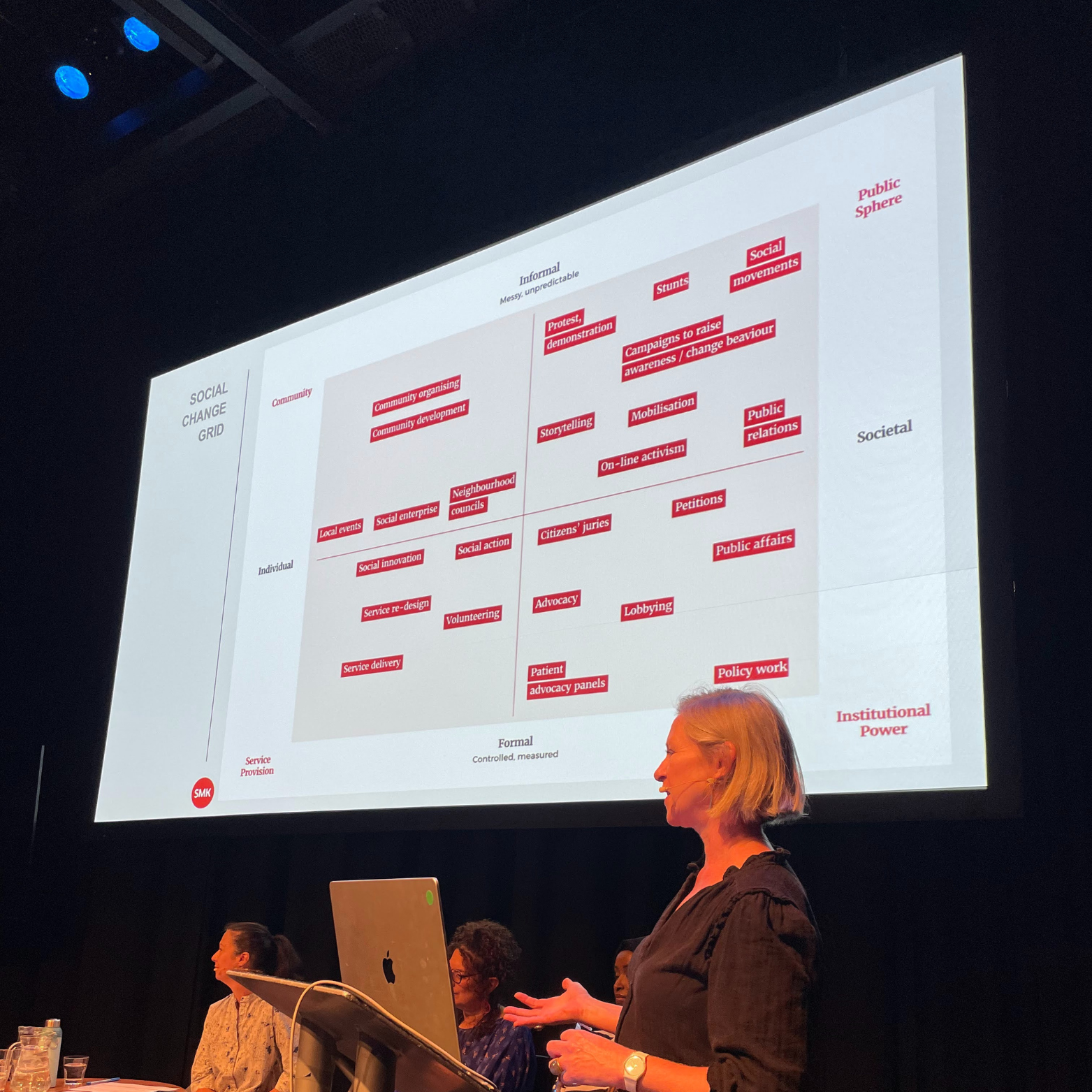

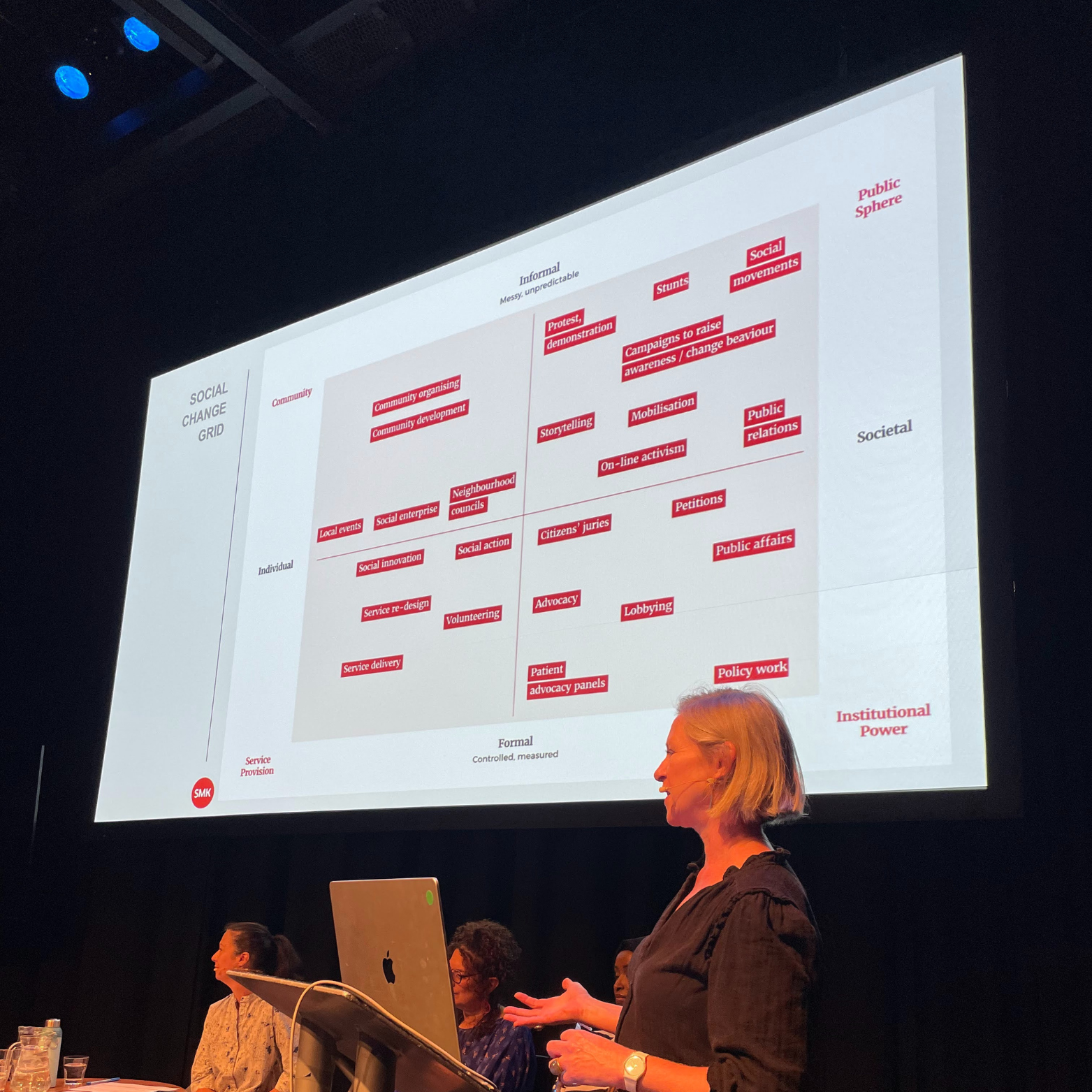

Three different projects were analysed with the ‘Social Change Grid’ created by Tibballs to better understand the leverage points, channels and opportunities for agency in what she describes as the ‘pinball game’ of changemaking in society. From formal to informal action and from individual to societal scale, the Grid’s four quadrants map how and where types of change takes places and, how changemakers mobilise, connect, build momentum and power.

The focus: housing crisis

We chose to focus on projects unified by a single theme for the purpose of comparison and contrast. Among the many intersecting and complex challenges we face, the cost of living, coupled with the crisis in affordable, safe housing continues to dominate public consciousness, with over 2.5 million younger adults known to be living in unfit housing conditions.

The artists

Our selected artists included creative campaigners the Yes Men, 360 VR filmmaker Dylan Valley and director Katja Esson.

Build Homes Now Belfast – the Yes Men

The Yes Men - who call themselves creative campaigning ‘tricksters’ - worked with local activists in Belfast to put pressure on the local council to cancel an investor-focused development project, asking instead for a focus on social housing.

They did this through a fake announcement at a big manufacturing conference, on bus stops and billboards throughout central Belfast, and, finally, at a groundbreaking and seed-bombing ceremony at one empty site. We spoke with Keil Troisi, one of their team, to better understand the project.

In their dissection of the project’s tools and tactics, Sue and Zamzam picked up on the Yes Men’s methods of subvertising and impersonation among a range of approaches in order to ‘turbo-charge’ existing grass roots activism.

From the density of simultaneous activity logged on the Grid’s four quadrants, it became clear that the dynamic injection of tactics, energy and confidence was key to gaining media attention and traction. This, combined with a willingness and ability to take risks and infiltrate structures of power, given their status as ‘outsiders’ operating at arm’s length. The local campaigners could have been vulnerable to more serious consequences had they been more directly implicated in some of the actions.

In what they refer to as ‘multi-platform creative collaboration’ through ‘participation and the practice of rights’, creativity, determination, and humour are the hallmarks of the Yes Men’s ‘trickster’ anti-authoritarian approach, as well as resourceful and skilful navigation of the issues and obstacles they tackle. Although aspects of their activity are similar to campaigning or community organising, it appears to be the crafting and weaving together of multiple, mutually reinforcing activities, delivered with the flair and audacity of professional performers that sets them apart.

Razing Liberty Square – Katja Esson

Developed over many years with the community of Miami’s Liberty City, Esson’s documentary film raises awareness of the ‘climate gentrification’ at the intersection of environmental crisis and housing justice. Liberty City was one of the oldest public housing projects in Florida. With sea levels rising in Miami, the residents found themselves battling a government-backed revitalisation project, with property developers trying to cash in on land which sits on higher ground and so does not flood.

The discussion around Razing Liberty Square emphasised the central importance of the sustained engagement of the filmmaker with the community over several years – and which is still ongoing. Building a foundational relationship of trust is more commonly seen in campaigning than in creative projects that can appear to ‘parachute’ in because of funding timelines and limitations, commissioning parameters and other pressures. In ways not dissimilar to the shortcomings in the humanitarian sector, the result of short-term interventions can sometimes be negative in that hope and agency is kindled, then withdrawn or left to atrophy.

Although Esson claims that she set out from a personal motivation simply to tell a story that moved her, through the exercise she came to see herself as a ‘reluctant activist’ whose project clearly catalysed and reinforced the community movement to raise awareness around their plight. A combination of other factors and agents, including the attention of city lawmakers and media interest also came to play a role.

No Place But Here - Dylan Valley & Annie Nisenson

The third piece we dissected was the 360 VR film No Place But Here, which was shown as part of the Alternate Realities exhibition at site gallery.

The VR piece features stories from a working-class community in the gentrifying area of Woodstock, Cape Town, who take over and occupy a disused hospital. It is the only way they can avoid being displaced from the area they call home.

No Place But Here was partly funded by Meta, on the basis of its creative use of new technologies. The filmmakers used part of that funding to pay the residents a ‘location fee’ and also redirected screening fees to the community – Valley describes this as a show solidarity with the movement. The film was shared openly within the community, with guided tours and guerrilla screenings. Social media was used to spread the word about the project and Valley’s own profile and credibility also helped to bolster the awareness campaign.

The film offered human stories that contrasted with the dominant narrative around Occupy members. The project’s stated intent was to shift public perception and connect with a global movement.

By contrast to Razing Liberty Square, whose director is German, the No Place But Here team have a personal connection to the region and communities they sought to document. Arguably this allowed for a more natural relationship of trust with the residents. Dylan Valley’s standing as a respected filmmaker with recognised credentials also raised the status of the project and the residents, leading to talks with officials, a higher profile campaign and connection to the global Occupy movement.

Panel discussion

The three autopsies were followed by a panel discussion which included Alex Cooke, chair of the board of Sheffield DocFest, founder & CEO of Renegade Stories who have previously worked with the Yes Men on their film Yes Men Fixing the World. Cooke was also the Executive Producer of Channel 4 Doc ‘UNTOLD: Help My Home Is Disgusting’ with Kwajo Tweneboa. Tweneboa has developed his own extremely successful approach of using storytelling to lobby for change using social media.

The panel discussed the ongoing challenge of tracking the impact of creative interventions in an interwoven cultural landscape where causal relationships are hard to pin down. The campaigners in the group underlined the importance of storytelling in growing public consciousness and winning support, bringing life to training in community settings, inspiring campaign actions and standing out in a policy sphere dominated by facts, figures and reports. Free and easy access to powerful content without the obstacles of paywalls, passwords or exclusive hardware (such as VR headsets) was underlined.

The discussion also helped to crystallise the findings of the autopsy exercise.

The first finding was the surfacing of different types of impact: often in the arts and media this focuses on the interaction with the artefacts after the work is finished (numbers of people who have watched a work, media hits etc) but this grid values many part of the pre-production process as impact too. These are not aspects of impact typically recognised or expected in grant applications.

Secondly, time is a factor: impact is complicated, interwoven and can’t be rushed. Trust, in particular, can take time to build and is crucial ingredient of collaboration and co-creation.

Third was that change is neither linear, nor a simple list of bullet points, but an ecosystem. The Grid helped to structure and visualise that. And like any ecosystem, one thing catalyses another. Feedback loops occur. Momentum builds and tipping points are reached. Change is relational. To more accurately map impact, it’s crucial to show the other agents and factors involved, not just the outputs and metrics of a given project or intervention. Each individual project can connect to a larger campaign to become part of a much larger movement. And by better understanding their position and role in a complex system, creatives and campaigners alike can leverage and maximise their potential for impact as part of that wider ecosystem of change.

Want more?

Find out about the Horizon Impact Lab – a week-long series of workshops aiming to boost the impact and reach of an intimate theatre piece exploring climate change.