Disability History Month: Going Beyond the Visual

- Written byNicole Horgan

- Published date 19 December 2024

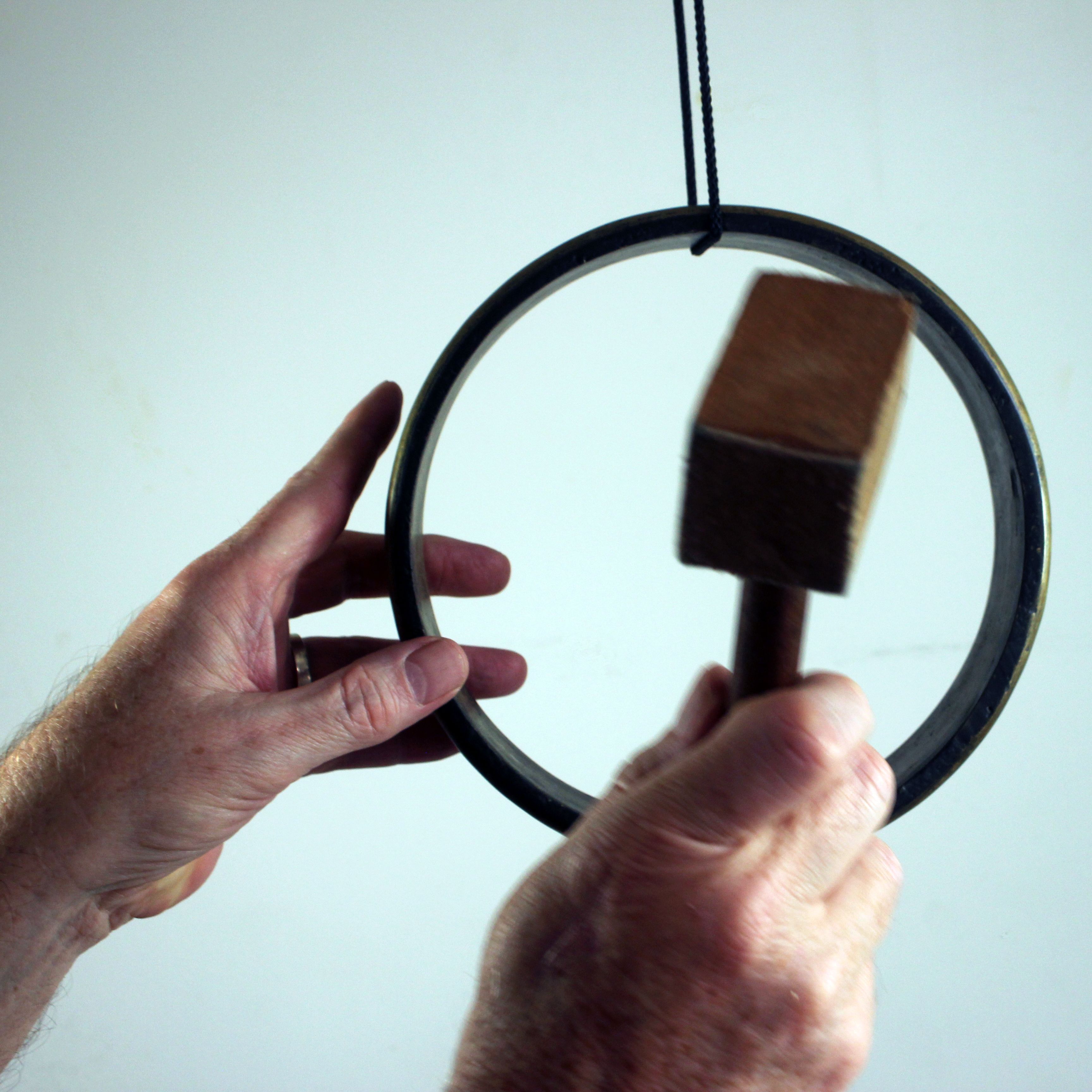

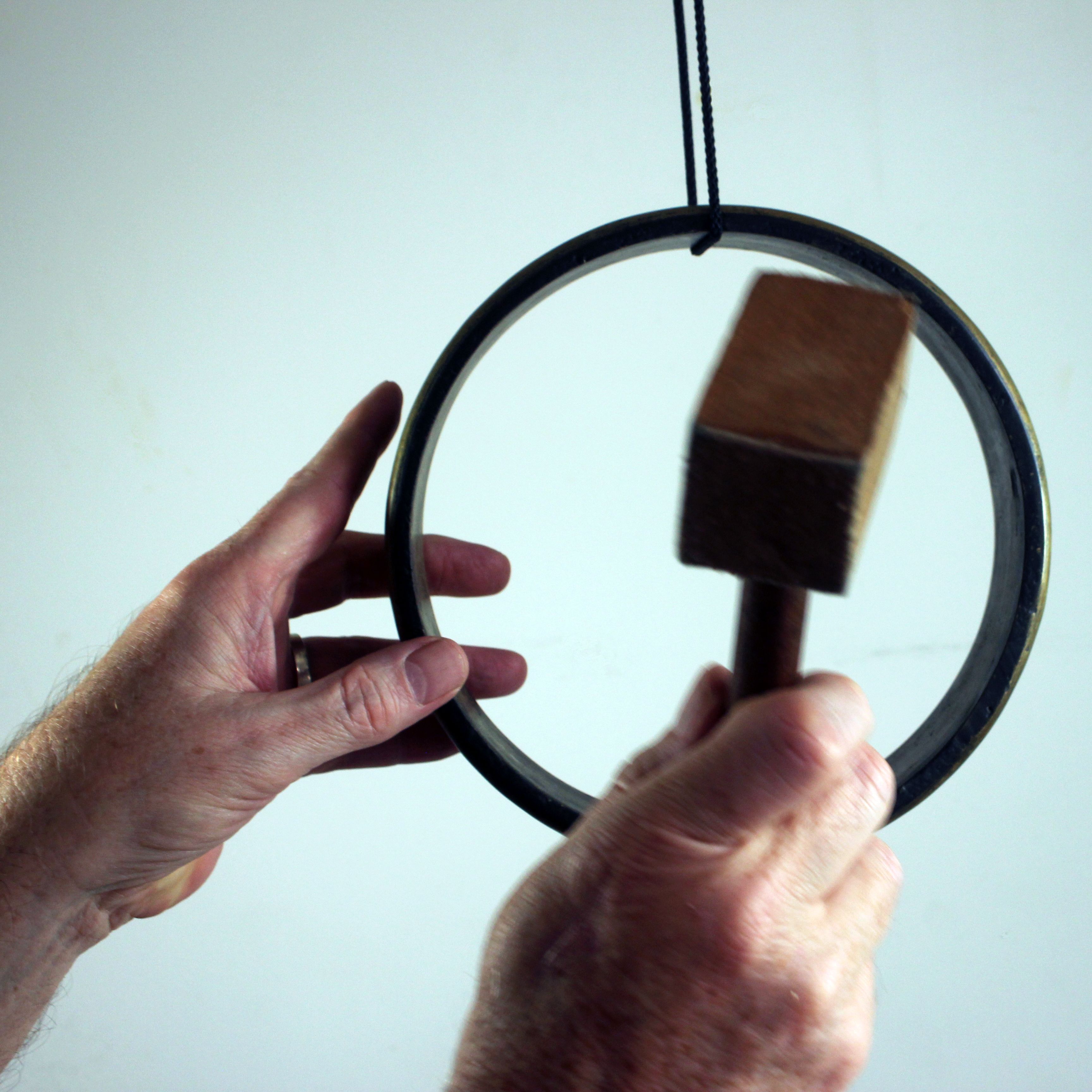

Most exhibitions exclude blind and partially blind audiences, often with rules against touching the artwork. Beyond the Visual is a pioneering project that seeks to challenge this norm by embracing touch, sound, and movement, redefining how art is experienced in gallery and museum settings.

The initiative is led by Dr. Ken Wilder, Professor of Aesthetics at the University of the Arts London (UAL), and Dr. Aaron McPeake, artist and Associate Lecturer at Chelsea College of Arts. Together, they’ve joined forces with the Henry Moore Institute and Shape Arts to push the boundaries of sensory perception in art through this project.

In this interview, Ken and Aaron share insights into their collaborative journey, the motivations behind the project, and their vision for a more inclusive future in art.

Can you tell us a bit about yourselves and your professional background?

Aaron McPeake: My journey into the arts took a significant turn after I became legally blind in 2002. Before that, I worked as a stage lighting designer, but losing my sight meant I had to rethink my career. I returned to education, starting at Central Saint Martins, and eventually completed my PhD at Chelsea College of Arts. I’ve been teaching at UAL as an Associate Lecturer since 2006. My blindness has profoundly shaped my approach to art, emphasising the importance of sensory engagement. My work is not about compensating for sight; it’s about exploring how sound, touch, and even smell can deepen the experience of art.

Ken Wilder: My background is in architecture and interior design, and I’ve been teaching at Chelsea College of Arts for 30 years. My practice focuses on the relationship between space, sensory perception, and artwork—how sound, touch, and spatial dynamics interact to create a more holistic engagement with art.

What inspired your collaboration and how did Beyond the Visual come to life?

KW: The idea for Beyond the Visual really emerged from the fact that both Aaron and I are practitioners. We overlapped during our PhDs at Chelsea College of Arts, and we collaborated on a project in Sweden in 2017, creating a piece called Circumstances in a church designed by Sigurd Lewerentz. Working together, we realised we both had an interest in the relationship between space and the artwork, and how perception plays a role in that. But we were particularly focused on perceptions that went beyond just the visual sense. These shared interests laid the groundwork for Beyond the Visual.

AM: Yes, our collaboration grew out of these mutual interests. We were both fascinated by the sensory elements of art—how touch, sound, and even smell could be integral to experiencing it. This naturally led to thinking about how we could push those boundaries further and challenge the dominance of sight in gallery settings.

KW: We started to think: what happens when engagement with art starts from an acknowledgment of the diversity of perceptual abilities? People perceive the world in different ways. People have different bodies and ways of engaging with art. Instead of assuming a “universal” beholder, we began to explore what happens when we overturn that idea. What if everyone could benefit from considering different ways of engaging with art through different senses?

How did you go about securing funding for this project?

KW: We put in a bid for the Arts and Humanities Research Council's Exhibition Fund, which is a major grant of £250,000. There was one award, and we won it. That funding helped us create a whole network of blind and partially blind artists, and it enabled us to work with some fantastic partner organisations like Tate, the Wellcome Collection, the Henry Moore Institute, Shape Arts, Vocalise, and Disordinary Architecture projects. Our network raised a lot of important questions, which are now directly feeding into the curatorial process for an exhibition that’s happening next year at the Henry Moore Institute in November 2025.

What do you see as the most valuable aspect of this project?

KW: For me, it’s about the potential for what we call “blindness gain.” This is the idea that by creating multisensory art, we’re not just making it accessible for blind and partially blind people but enhancing the experience for everyone. Access and inclusivity shouldn’t be afterthoughts—they should be at the core of how art is presented and experienced.

AM: What’s valuable here is the opportunity to rethink curatorial practices and policy. We’re proposing new ways to engage with sculpture and installation, where the emphasis is on multisensory access. This is not just about providing accommodations—it’s about enriching the way all audiences interact with art.

How will the findings from the project shape the upcoming exhibition?

AM: We’ve established three key rules: accessibility at every stage, a majority of blind or partially blind artists, and all works being multisensory. We’re still finalising the artist list, but the exhibition will challenge traditional gallery conventions from the moment visitors approach the space. We’re rethinking everything—navigation, description, and how people interact with the artworks.

KW: We’re also rethinking audio description. Rather than the typical authoritative voice, we’re exploring ways to include multiple perspectives. For instance, an eight-year-old’s reaction to a piece might be as valuable as the artist’s. This approach challenges the hierarchy of interpretation and encourages a richer dialogue between art and audience.

What impact do you hope this project will have beyond the exhibition?

KW: What’s particularly valuable in terms of a lasting legacy for the project is its potential to shift curatorial policies and conventions, especially in how people engage with sculptural practice within museum contexts. We’re already seeing institutions like the Henry Moore Institute adopting some of our findings into their policies. The idea is to integrate these principles into the fabric of how art is presented.

AM: And it’s not just limited to the UK. Through our network, we’ve engaged with institutions in North America, Australia, and beyond. While we’re not claiming to change the world, we’re contributing to a broader conversation about accessibility in the arts—and that’s a powerful step forward.

Find out more about this project:

Beyond the Visual: Non-sighted Modes of Engaging Art

Beyond the Visual: Blindness and Expanded Sculpture