By Aimee Crickmore, MA Conservation, Camberwell College of Arts

Postgraduate Community Ambassador Aimee Crickmore is a student on the MA Conservation course at Camberwell College of Arts and she recently got in touch with the PG Community Team to ask if we would be interested in publishing an article about conservation considerations for the display of art works. Of course we were!!!….. this is an important topic for many creatives today and we are very grateful that Aimee took the time to share some of her top tips with you here.

-

Light

It’ll be no news to you that the conditions in which an object is lit can produce dramatically different effects, and can even alter how vibrant media appears! ‘Natural’ light from the sun is widely considered to be optimal for viewing, but the important thing to remember is that ALL light across the electromagnetic spectrum is damaging and cumulative!

Most gallery spaces tend to use fluorescent Tungsten lighting, which is great; it’s pretty cheap, and relatively reliable, and has the edge on natural lighting as it can in theory run as long as you like (whereas the light cast by the sun is dependent on the size of aperture (think windows), any obscuring buildings, and er… time of day!) but unless precautions are taken, media can fade (or darken) quite rapidly!

To reduce these risks, limits can be placed on light exposure (the recommended ‘exposure limit’ for sensitive materials such as watercolour is 50 lux, whereas more robust materials like oil-paint have a suggested exposure limit of 200 lux, and is worth bearing in mind for more long term exhibition). For reference, the current specifications for the National Gallery as of publication are:

Light level: 150 ± 50 lux (UV radiation content now specified as less than 10 μW/lumen; formerly 75 μW/lumen)

Annual light exposure limit: 650 kilolux hours

Relative humidity: 55 ± 5 %

Temperature 21 ±1°C (winter); 23 ± 1°C (summer).

Light levels can be measured using a device called a ‘Lux Meter’ (‘lux’ is the unit of measurement for illuminance) for more bespoke, long-term exhibition but for temporary, short-term display, moderating exposure and ensuring all lights are turned off after hours is likely all that may prove achievable. If possible transparent UV-filter sheets can be applied to glass-display cases, and windows and can significantly reduce the damage.

Sources: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/caring-for-the-paintings/paintings-and-their-environment?viewPage=4 (Accessed 7/1/17)

Garry Thomson, Museum Environment, 1986

2. Display

There’s an ideal in Conservation known as ‘The Black Box’. Sounds ominous, I know, but the big idea is that an item stored in total darkness, in a box, deprived of oxygen and stored at a low temperature will last indefinitely.

Of course, this isn’t practical for art on exhibition but the next best thing is to ensure that the rate of deterioration is slowed by using Conservation-grade materials for mounting or backing of art.

As a general guide, selecting paper, card or mount-board with a high cellulose fibre count translates as a more long-term investment in the items ‘useful lifetime’, and more in depth information on selecting appropriate materials may be accessed here:

http://www.conservationregister.com/PIcon-Mounting.asp

Though pressure sensitive tape is affordable, easily-purchased and ready to use when hanging displays, it’s worth knowing that it is one of the biggest pains for paper and book conservators alike! They work by having an adhesive carrier which penetrates the surface to which it is applied, and are very challenging to remove without the use of solvents! They also discolour with age and with time can cause paper to become brittle and translucent.

3. Environment

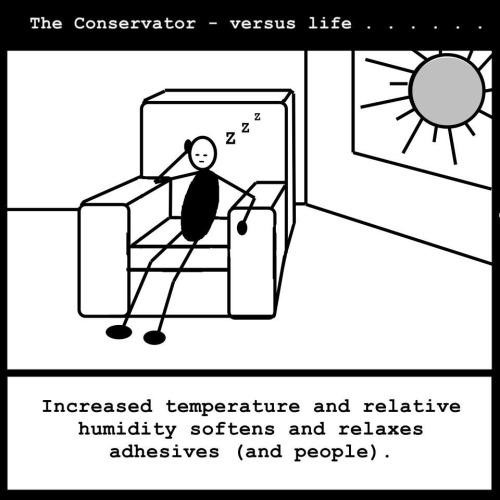

The above comic strip by Shellie Cleaver is part of a series of comics named ‘The Conservator Versus Life’ which debuted in 2013 and centered on finding humour in everyday problems from a Conservation perspective.

In terms of approach, many of the problems discussed here share interconnected elements, for example; when an electric light is turned on, this obviously illuminates the artwork, but the energy involved in that chemical reaction means that in addition to causing fading, heat is also emitted. The more light sources, the more of an impact this may have on overall temperature.

Environmental controls do encompass the regulation of light, temperature and relative humidity (the amount of moisture present in a given environment, expressed as a percentage of the capacity, after which point condensation of moisture will occur), which if left unchecked may damage art, but they also include the management of items themselves, to prevent accumulation of surface particulates like dust.

Galleries and Museum spaces typically have their own buildings management systems which track fluctuation in temperature and humidity, but though accurate these are expensive and not really suitable for more temporary exhibition spaces. If you are exhibiting in such a location, try to avoid exhibiting art above or near a radiator, as these are likely to cause damage.

For reference, the current general guidelines for temperature and relative humidity in exhibition spaces should not drop below 13 – 20° C but can be between ‘15–25°C with allowable fluctuations of +/-4°C per 24 hour period’ (IIC, 2015) with a relative humidity range within 45

-55% with an allowable fluctuation of +/- 5% per 24 hour period (IIC, 2015).

These guidelines fall within acceptable parameters for most materials, but these may differ for material on a case by case basis. If you are concerned about the sensitivity of a material, you can find the MA Conservation students at the Conservation studios on the Camberwell site!

Sources:

http://theconservator.tumblr.com

https://www.iiconservation.org/node/4938

https://www.iiconservation.org/node/5168

PD5454: 2012

4. Longevity

Experimentation is an organic part of developing an artistic style, but it must be recognised that some materials are inherently more vulnerable than others. Plastics, for example, may yellow, embrittle, off-gas or even deform when exposed to heat, with volatile materials like cellulose nitrate carrying an inherent risk of spontaneous combustion.

By asking how long you want your art to last, it can help you make informed creative decisions – incorporating processes of decay can often be an interesting and thought-provoking aspect to introduce to a piece, but if it is caused unintentionally it can be very distressing!

In that vein, when you select paint it may be useful to look for the ‘light fastness’ rating; this value indicates the resistance to change in response to light, and the better this value is the more vibrant the media may be expected to remain post-application.

This may appear on the paint tube as the ASTM rating (ranging from I – excellent lightfastness, to III – poor lightfastness) or the BS rating (the most lightfast value is 8). This information is often made readily available on the website of the manufacturer.

Sources:

http://www.winsornewton.com/uk/discover/resources/composition-permanence

5. Does it really matter to you?

For conservators the answer to this question is a definitive ‘yes’; ensuring objects are preserved for generations to come is a key priority but the creative process may not always align with this aim!

How much time you spend considering these issues really depends on your intent – if you want to make sure your art will be preserved after your lifespan, it’s definitely worth taking some time and consulting with a conservator if you have questions!

However, many artists engage with biodegradable materials to provoke a response or explore conceptual themes. ‘Auto-destructive’ art, a term coined by Gustav Metzger in 1962, engages with the idea that destruction and decay can itself be creative.

Wherever the creative process takes you, I hope this article has been interesting and informative!

Sources:

http://beautifuldecay.com/2010/07/21/green-art-10-artists-working-with-recycled-materials/

http://www.tate.org.uk/learn/online-resources/glossary/a/auto-destructive-art

http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/seeds-destruction

Interested in writing an article for the PG Community blog? … Get in touch with the PG Community Team with your ideas via email PGCommunity@arts.ac.uk